Abstract

Background

Alcohol-related harm has been found to be higher in disadvantaged groups, despite similar alcohol consumption to advantaged groups. This is known as the alcohol harm paradox. Beverage type is reportedly socioeconomically patterned but has not been included in longitudinal studies investigating record-linked alcohol consumption and harm. We aimed to investigate whether and to what extent consumption by beverage type, BMI, smoking and other factors explain inequalities in alcohol-related harm.

Methods

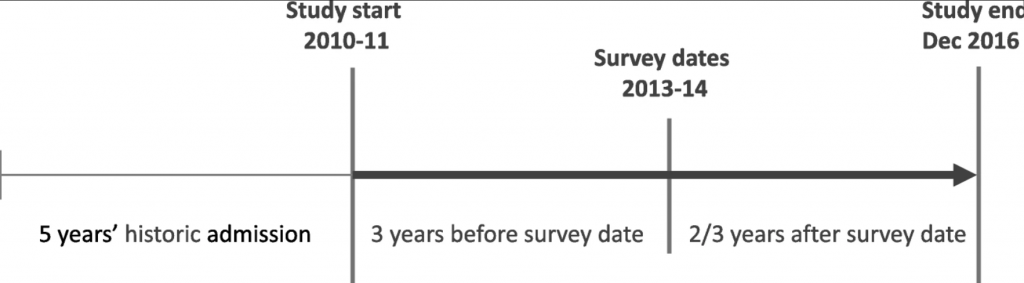

11,038 respondents to the Welsh Health Survey answered questions on their health and lifestyle. Responses were record-linked to wholly attributable alcohol-related hospital admissions (ARHA) eight years before the survey month and until the end of 2016 within the Secure Anonymised Information Linkage (SAIL) Databank. We used survival analysis, specifically multi-level and multi-failure Cox mixed effects models, to calculate the hazard ratios of ARHA. In adjusted models we included the number of units consumed by beverage type and other factors, censoring for death or moving out of Wales.

Results

People living in more deprived areas had a higher risk of admission (HR 1.75; 95% CI 1.23–2.48) compared to less deprived. Adjustment for the number of units by type of alcohol consumed only reduced the risk of ARHA for more deprived areas by 4% (HR 1.72; 95% CI 1.21–2.44), whilst adding smoking and BMI reduced these inequalities by 35.7% (HR 1.48; 95% CI 1.01–2.17). These social patterns were similar for individual-level social class, employment, housing tenure and highest qualification. Inequalities were further reduced by including either health status (16.6%) or mental health condition (5%). Unit increases of spirits drunk were positively associated with increasing risk of ARHA (HR 1.06; 95% CI 1.01–1.12), higher than for other drink types.

Conclusions

Although consumption by beverage type was socioeconomically patterned, it did not help explain inequalities in alcohol-related harm. Smoking and BMI explained around a third of inequalities, but lower socioeconomic groups had a persistently higher risk of (multiple) ARHA. Comorbidities also explained a further proportion of inequalities and need further investigation, including the contribution of specific conditions. The increased harms from consumption of stronger alcoholic beverages may inform public health policy.

Background

Alcohol consumption is a leading risk factor for population health worldwide [1]. Measures of alcohol-related harm such as hospital admissions and mortality show particularly wide inequalities and reducing inequalities is a focus of governments [1,2,3,4]. Alcohol-related harm has been found to be higher in disadvantaged groups, despite comparable or even lower reported alcohol consumption than in advantaged groups [5, 6]. This phenomenon has been termed the ‘alcohol harm paradox’. A number of hypotheses to explain it have been suggested in the literature [5, 7,8,9].

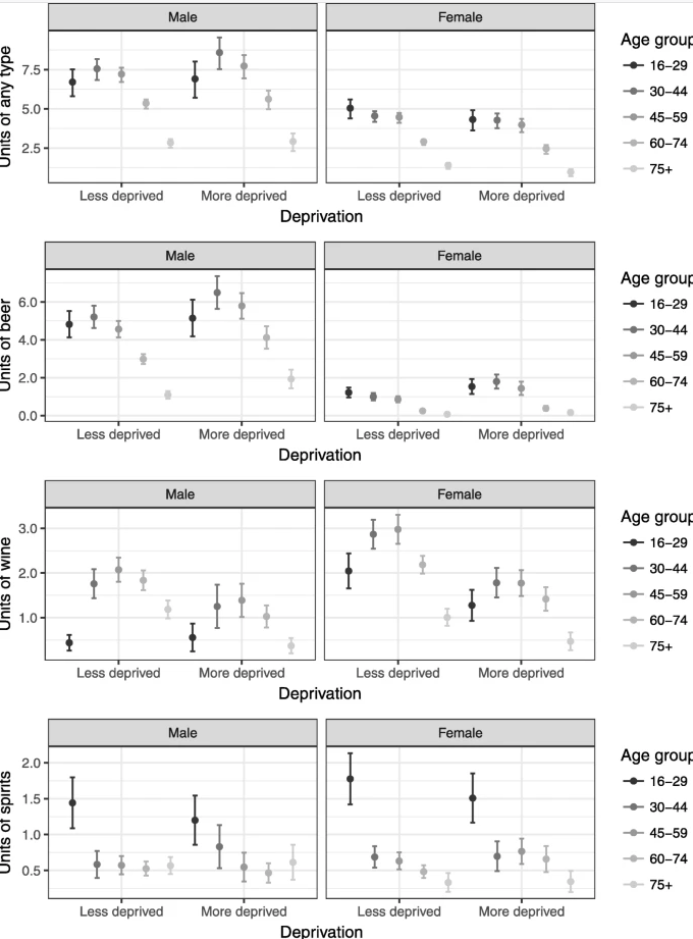

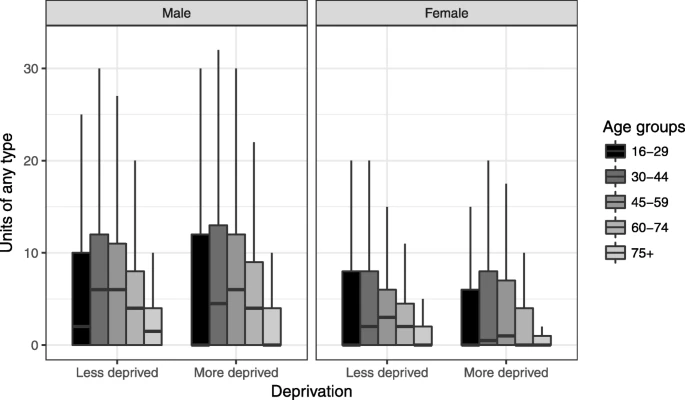

The first hypothesis is that there may be different patterns of alcohol consumption across groups rather than simply unit consumption or whether a threshold of consumption is reached. Overall, average consumption may not differ between groups but if all alcohol is consumed in one sitting peak toxicity is greater in those who binge drink. More deprived groups are more likely to drink at extreme levels, potentially in part explaining the paradox [8]. The type of alcoholic beverage may also offer an explanation. Consumption of spirits or beer has been associated with worse “trouble per litre” than wine, and consumption of spirits have been associated with increased alcohol poisoning and aggressive behaviour [10, 11]. It has also been suggested that the poorest outcomes are found for beverages chosen by young men [10]. A potential mechanism could be the faster absorption of alcohol from stronger drinks or other characteristics of the people with a particular beverage preference, but the reasons for differing outcomes by beverage type are not well understood.

The second hypothesis concerns the combination of challenging health behaviours or comorbidities typically found in more disadvantaged groups. This combination causes proportionately poorer outcomes compared to similar alcohol consumption in advantaged groups. Deprived higher risk drinkers were found to be more likely to drink alcohol combined with other “health-challenging behaviours that include smoking, being overweight, poor diet and lack of exercise” compared to more affluent groups [7]. There are also known associations between mental health and alcohol consumption which could affect disadvantaged groups differently [12].

The third hypothesis relates to underestimating consumption in disadvantaged groups and the alcohol harm paradox not existing or being an artificial construct. Response bias may be at work where those who do not respond to the survey could have systematically different consumption levels or worse outcomes compared to responders [13]. Moreover, current drinking may not reflect the life history of harmful drinking, which has been found to be associated with deprivation in lower and increased risk drinkers [7].

A few recent cross-sectional studies have investigated the harm paradox, but mostly considered drinking patterns and their influence on the paradox rather than outcomes of harm [7, 8]. Only one longitudinal study in Scotland has employed record-linkage between consumption patterns and harm, investigating socioeconomic status as an effect modifier, but did not include the type of beverage or multiple admissions [5].

This study aims to investigate whether and to what extent individual alcohol consumption by type of beverage, smoking, BMI and other factors could account for inequalities in alcohol-related hospital admission (ARHA). A different risk of harm by socioeconomic group for a given level of individual consumption could be an explanation of the alcohol-harm paradox at group level. Additionally, we examine how the patterns of consumption by type of beverage differ by socioeconomic group.

Methods

Data

This analysis was carried out using the Electronic Longitudinal Alcohol Study in Communities (ELAStiC) data platform and details on the data and linkage methods are outlined in the study protocol [14]. A summary and further specific details for this study are described below.

Welsh health survey

Our cohort consisted of 11,038 people aged 16 and over who responded to the Welsh Health Survey in 2013 and 2014, consenting to have their survey responses linked to routine health data. The Welsh Health Survey is an annual population survey on health and health-related lifestyle based on a representative sample of people living in private households in Wales (random sampling). It consists of a short interview with the head of household and a self-completed questionnaire for each individual adult aged 16 years and above in the household. A question on consent for data linkage was included from April 2013 to December 2014 and approximately half of the respondents agreed. Originally 11,694 respondents agreed to their data being linked, and records were successfully linked and anonymised into the SAIL Databank through standard split file processes for 11,320 individuals (3.2% loss) [14]. Linkage to records of household residence needed for analysis failed for 282 respondents, resulting in the final sample of 11,038 people (5.6% loss overall). An overview of characteristics of the study population is shown in Table 1.

Table 1 Characteristics of the study population

| Men | Women | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Survey year | |||

| 2013 | 1906 (37%) | 2269 (38%) | 4175 |

| 2014 | 3199 (63%) | 3664 (62%) | 6863 |

| Age group | |||

| 16–29 years | 716 (14%) | 998 (17%) | 1714 |

| 30–44 years | 914 (18%) | 1202 (20%) | 2116 |

| 45–59 years | 1277 (25%) | 1522 (26%) | 2799 |

| 60–74 years | 1518 (30%) | 1502 (25%) | 3020 |

| 75+ years | 680 (13%) | 709 (12%) | 1389 |

| Area deprivation | |||

| More deprived 40% | 1826 (36%) | 2170 (37%) | 3996 |

| Less deprived 60% | 3279 (64%) | 3763 (63%) | 7042 |

| Alcohol consumption* | |||

| None | 526 (10%) | 854 (13%) | 1380 |

| Not binge | 3041 (64%) | 3740 (69%) | 6783 |

| Binge | 1440 (26%) | 1197 (18%) | 2637 |

| Mean units (drinkers only) | |||

| Beer or Cider | 6.3 (6.7) | 1.6 (3.7) | 4.0 (6.1) |

| Wine or Champagne | 2.1 (4.1) | 3.8 (4.7) | 2.9 (4.5) |

| Spirits or other | 1 (2.7) | 1.5 (3.1) | 1.2 (2.9) |

| Any type | 9.5 (7.8) | 6.9 (5.8) | 8.2 (7.0) |

| Smoking status* | |||

| Never smoker | 2242 (44%) | 3073 (52%) | 5315 |

| Ex-smoker | 1837 (36%) | 1670 (28%) | 3507 |

| Smoker | 972 (19%) | 1136 (19%) | 2108 |

| Mean BMI (SD) | 27.2 (4.84) | 27 (5.94) | 27.1 (5.4) |

| Total person-years | 29,221.1 | 34,417.8 | 63,638.9 |

| Number of admissions | 169 | 110 | 279 |

Table 4 Comparison of regression model results: hazard ratios for the risk of alcohol-related hospital admission for each socioeconomic measure

| Events | Person-years | Basic model | Adjusted model | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI; p-value) | HR (95% CI; p-value) | |||

| i) Area deprivation (Model A/B) | ||||

| Less deprived 60% (ref) | 148 | 39,801.1 | 1 | 1 |

| Most deprived 40% | 131 | 23,837.7 | 1.75 (1.23–2.48; 0.002) | 1.48 (1.01–2.17; 0.043) |

| ii) Social class (NSSEC) | ||||

| Professional and managerial (ref) | 80 | 25,623.1 | 1 | 1 |

| Intermediate | 39 | 11,277.2 | 1.52 (0.86–2.7; 0.152) | 1.3 (0.67–2.52; 0.436) |

| Routine and manual | 146 | 25,297.1 | 2.03 (1.3–3.15; 0.002) | 1.81 (1.09–3; 0.022) |

| Never worked/long-term unempl. | 14 | 1441.5 | 5.65 (2.49–12.82; < 0.001) | 4.04 (1.55–10.51; 0.004) |

| iii) Employment | ||||

| Employed (ref) | 36 | 30,724.8 | 1 | 1 |

| Not employed | 243 | 32,914.1 | 3.87 (2.24–6.69; < 0.001) | 3.38 (1.97–5.65; < 0.001) |

| iv) Housing Tenure | ||||

| Home owner (ref) | 127 | 47,376.9 | 1 | 1 |

| Private rental | 15 | 7104.5 | 1.13 (0.56–2.27; 0.729) | 1 (0.49–2.07; 0.992) |

| Social rental | 137 | 9154.4 | 3.97 (2.73–5.77; < 0.001) | 2.89 (1.9–4.42; < 0.001) |

| v) Highest qualification | ||||

| Degree (ref) | 66 | 11,254.9 | 1 | 1 |

| Other | 117 | 39,486.6 | 1.25 (0.72–2.15; 0.428) | 1.03 (0.57–1.84; 0.926) |

| None | 96 | 12,897.4 | 2.38 (1.32–4.31; 0.004) | 1.78 (0.93–3.4; 0.083) |

Adjusting for the total number of units regardless of type of beverage (results not shown) gave very similar results to Model B with an elevated risk of ARHA in the most deprived group (HR 1.46; 95% CI 1. 01–2.11). This suggests that the type of beverage was not important over and above the number of units relating to inequalities.

For models C and D the risk of ARHA in the more deprived group was reduced further compared to Model B (Poor health by 16.6%: HR 1.36; 95% CI 0.92–2.00; being treated for mental health condition by 5.0%: HR 1.45; 95% CI 0.96–2.17, Table 5). This risk in disadvantaged groups, although still elevated, was not statistically significant. Although this will need further research relating to interactions and specific conditions, it suggests that comorbidities, either relating to alcohol or otherwise, could be important.

Table 5 Results of regression models for area deprivation investigating comorbidities: hazard ratios for the risk of alcohol-related hospital admission for each model covariate

| Adjusted model, including general health (Model C) | Adjusted model including treated for mental health condition (Model D) | |

|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI; p-value) | HR (95% CI; p-value) | |

| Men (ref) | 1 | 1 |

| Women | 0.71 (0.47–1.06; 0.092) | 0.63 (0.42–0.95; 0.026) |

| Less deprived 60% (ref) | 1 | 1 |

| More deprived 40% | 1.36 (0.92–2.00; 0.120) | 1.45 (0.96–2.17; 0.074) |

| Number of historic adm. | 1.35 (1.22–1.48; < 0.001) | 1.35 (1.23–1.47; < 0.001) |

| Units beer and cider | 1.03 (1–1.05; 0.052) | 1.02 (0.99–1.04; 0.197) |

| Units wine and champagne | 1.03 (1–1.07; 0.068) | 1.03 (0.98–1.07; 0.239) |

| Units spirits and other | 1.07 (1.02–1.13; 0.009) | 1.06 (1.01–1.12; 0.025) |

| Never smoker (ref) | 1 | 1 |

| Ex-smoker | 1.38 (0.83–2.32; 0.216) | 1.48 (0.88–2.51; 0.141) |

| Smoker | 4.10 (2.56–6.56; < 0.001) | 3.88 (2.37–6.35; < 0.001) |

| BMI | 0.97 (0.93–1.01; 0.101) | 0.98 (0.94–1.02; 0.257) |

| Good health (ref) | 1 | |

| Poor health | 2.89 (1.91–4.37; < 0.001) | |

| Not treated for mental health condition (ref) | 1 | |

| Treated for mental health condition | 2.66 (1.72–4.11; < 0.001) |